By M Ghazali Khan

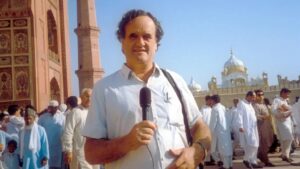

Sir Mark Tully, the former veteran BBC journalist in India, died in Delhi on 25 January 2026 and was cremated there.

I don’t remember how much I could really understand the news at the age of seven or eight, but I do remember that my late grandfather, my late uncle, my father, and other relatives used to listen together in the evenings to the BBC Urdu Service on the radio. As far as I recall, besides the news, its current affairs programme Sair-e-Bain was very popular, and I still remember the phrase used in it: ‘Delhi se Mark Tully ka murasla’ (A dispatch from Mark Tully in Delhi).

For a long time, Mark Tully and the BBC were synonymous in South Asia. The level of trust placed in both can be gauged from an incident Mark Tully himself mentioned in his book Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi’s Last Battle (p. 4). He wrote:

‘One of those who listened to the BBC for news of the Prime Minister’s assassination was her only surviving son, Rajiv. On 31 October, he was campaigning for the Congress (Indira) Party in the Hooghly Delta below Calcutta… There he tuned to the twelve-thirty bulletin of the BBC World Service to hear Satish Jacob report that Mrs Gandhi’s condition was grave. A few minutes later, Satish Jacob confirmed to London that the Prime Minister had died. Rajiv Gandhi flew from Calcutta to Delhi…’

Mark Tully was undoubtedly a big name in the world of journalism, but for some reason, I always felt that in his reporting from India, his portrayal of Muslims carried much the same tone as that of the Indian mainstream media of the time. In those days, ‘Andh Bhakts’ (blind devotees) and ‘Godi media’ (lapdog media) had either not yet entered journalism or, like the government of the time, did not openly express their bias. However, the slant of the news was quite one-sided, though presented with great politeness.

Although many Indian Muslims do not agree with the reaction of the Muslim Personal Law Board in the wake of the infamous Shah Bano case—and the community is still paying a heavy price for that folly—what I remember is that Mark Tully, or his colleague Satish Jacob, described the number at a protest organised by the Board as so small that many Urdu newspapers strongly criticised the report.

The second incident one is reminded of occurred on 1 February 1986, when, following a Faizabad district court order, the Babri Masjid was reopened for worship. In BBC World Service news broadcasts from morning to evening, it was repeatedly reported that Muslims were protesting against the ‘reopening of a Hindu temple.’ Several friends and I called the BBC. When I spoke to the news editor and told him that what was being reported was false and misleading, he asked, ‘Then what should we say?’ I replied that the building, which had been unlocked for worship, was a historic mosque, but that if they wanted to show objectivity, they could at most call it a ‘disputed structure.’ He agreed, changed the wording in the final bulletin, and after the next bulletin, the story was dropped altogether.

Death is inevitable, and one day, everyone must depart from this world. Politicians, his former colleagues, and the general public have been praising Sir Mark Tully’s contributions and paying him rich tributes, which he undoubtedly deserves. But for some reason, obituary pieces written about famous people are often filled only with praise. A person’s private life is their own matter and should not be discussed; however, for personalities who have played a key role in shaping a country, a region, or an institution, or in writing its history, it is necessary to mention their shortcomings along with their virtues.